Tea With Milk

- Guest Curator Zach Kano

- Apr 26, 2017

- 4 min read

A few weeks ago, I returned from a quick 5-day trip to Tokyo. It was early April. The cherry blossoms were just beginning to bloom and this was my first time in the country for more than a couple days. It was a trip of sunshine and strong, brisk spring winds. Amidst the crowded streets and alleyways of Shinjuku and Shibuya, I began to feel an unsettling feeling—a mix of calm comfort at odds with a glint of guilt. As a Yonsei (fourth-generation Japanese-American), this trip brought me to view my conception of my identity in a new way. Wherever I’ve travelled or resided prior to this trip I’ve been identified as Asian of some kind—despite being four generation removed from Japanese émigrés, my skin and facial features mask my American cultural identity; —this was, however, a new type of tension, one in which my two identities were inverted. And, although I have always asserted the identity of an American of mixed Asian heritage when asked where are you from, this experience pushed me to confront the tension of being viewed as a foreigner in the United States and feeling like a gaijin in Japan. This tension reminded me of Allen Say’s 1999 picture book, Tea with Milk.

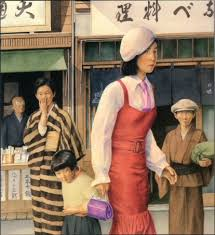

In Tea with Milk, Say explores identity in a way that most children identity books do not: he examines the struggle of a member of the Japanese diaspora to return to her ancestral homeland, rather than her struggle to assimilate to American culture. The protagonist, Masako, is about to finish high school when her parents decide to move back to pre-WWII Japan, after raising her in the San Francisco Bay Area. Once in Japan, Masako’s parents expect her to follow traditional Japanese customs: she is to learn fine crafts, like flower arranging and tea ceremony procedures, and marry a suitable man chosen by her parents. Masako rebels, finds her way to Osaka, acquires a job as a translator in a department store (thanks to her English and Japanese skills), and eventually marries Joseph (a Shanghainese banker who was raised by English parents). Joseph notices Masako’s American English accent and invites her out to have tea, which they both take with milk (an uncommon practice in mid-1900s Japan). She and Joseph develop a shared empathy over their feeling of un-belonging, their struggle to construct an identity in a culture that doesn’t feel to be their own. Say leaves his reader with this uneasiness of identity. The story concludes as Masako and Joseph decide to settle in Yokohama and start a family together—leading the author to reveal that these two are his parents.

On a brisk Wednesday morning, my boyfriend and I walked along the path leading to the Toshogu Shrine in Ueno Park. We walk amongst the hordes of sightseers, shoulder-to-shoulder, cheek-to-cheek, illuminated by diffused pastel pink and white light passing through the young umbrella of cherry blossoms. The street was lined with food vendors on either side: takoyaki, sukiyaki, charcoal-grilled river fish on a stick, okonomiyaki, karaage, and sweets. He stood in line to get a fish on a stick, I purchased okonomiyaki, and we sat ourselves at a wooden picnic bench under a tree. The sounds and the energy of the street festival reminded me of annual matsuri hosted at my grandmother’s church. I felt connected. Yet, I wondered to what extent I was tied to modern Japanese culture.

As I left Japan, I reflected on this feeling of un-belonging, feeling like a gaijin to some degree regardless of location. I thought about my family history: immigrating to the Hawaii at the turn of the twentieth century from southern Japan to work on sugarcane plantations. From these immigrant labor enclaves, a new community of its own developed, culturally distinct from the culture of its ancestral homeland. As mentioned in the fourth chapter, “Raising Cane: The World of Plantation Hawaii,” from Ronald Takaki’s Strangers from a Different Shore, Takaki highlights the movement of Asian immigrants to the island of Hawaii during the early 1900s: “In 1920, Asians totaled 62 percent of the island population, compared to only 3.5 percent of the California population and only 0.17 percent of the continental population” (1989, p. 132). On Hawaii, Japanese-American constituted 47.2 percent of the total population. As an American descendant of these early immigrants to Hawaii who grew up with a big plantation family on Kauai, the influence of plantation life—the mixing of Hawaiian, Chinese, Filipino, Korean, and American customs—created an identity unique to this new American community, yet vestigial ties to the homelands of émigré ancestors persisted through food, holidays, customs, family names, and physical features. As stated in his 2011 opinion piece from The Rafu Shimpo, “Into the Next Stage: Japanese American Newspapers: Over and Out,” George Toshio Johnson writes, “younger Japanese Americans are more culturally American than Japanese; while physical features will always distinguish even a typical mixed-race Japanese American from a White American, other than some dietary and vestigial cultural affiliations, a Yonsei or Gosei is simply another American.” By name and heritage, I am most definitely linked to Japan. However, the link is to a Japan that is since gone and my own lineage affected by growth and struggle as foreign-looking persons through the twentieth century.

Un-belonging, I believe, pushes Masako to take risks. Un-belonging can push us to become more reflective, critical thinkers as we try to form identity with and distinct from others. I’ve read Tea with Milk many times myself and many more times aloud with students. My hope is that children take Masako’s experience of wondering about her identity and where she can fit in as an example to continually evaluate their own lives and the identities they inhabit in many different situations.

Stay Backwords,

Zach Kano

Zach Kano is a 3rd grade teacher at a bilingual (Spanish-English) public school in urban Los Angeles. He lived for 5 years in San Francisco prior to Twitter moving their HQ to Mid-Market. He enjoys black coffee in the morning and tea in the afternoon (sometimes with milk).

Comments